"Youth is a state of mind"

Konosuke Matsushita's Message to Youth begins with this poem, "Youth." Throughout his life, Konosuke was passionate about helping young people grow, from his establishment of the Employee Training Institute to his personal funding of the Matsushita Institute of Government and Management shortly before his 85th birthday.

In 1965, at a coming of age ceremony in Kadoma City, the home of Matsushita Electric's Head Office, Konosuke told his audience, "If I could, I would give up everything to be your age again." Konosuke was interested in the development of the young, but he himself always wished to be youthful.

Despite the challenges he faced on becoming an entrepreneur, after his apprenticeships in Semba and his work for the electric light company, the founder worked with passion and opened a path to success. He was just 23 when he founded his company. What did Konosuke, who embarked on the path of the industrialist at an early age, convey about his way of life and thinking to the next generation? What were his hopes for them?

Let's trace the young Konosuke Matsushita's way of life and thinking, and study Konosuke's messages to new employees and young entrepreneurs on a wide range of occasions.

Note: This content has been edited for online presentation. It was originally presented in a special exhibition held at the Konosuke Matsushita Museum in the Panasonic Museum from February 6 to April 24, 2021, titled "A Message to Youth from Konosuke Matsushita."

Contents

In 1918, Konosuke Matsushita founded Matsushita Electric Housewares Manufacturing Works. He was 23 years old.

During the years leading up to the founding of his company, and during the turbulent times thereafter, he faced and overcame numerous challenges and grew as an individual.

Let's look back on young Konosuke's way of life and thinking.

Note: Konosuke Matsushita wrote an autobiography titled "My Way of Life and Thinking."

Konosuke leaves his apprenticeship at Godai Bicycle Shop to enter the world of electricity.

Konosuke leaves his apprenticeship at Godai Bicycle Shop to enter the world of electricity.

Forced to wait for a position to open at Osaka Electric Light Company, he goes to work at Sakura Cement Company.

A narrow escape: "I'm naturally lucky"

During his time at the Sakura Cement Company, Konosuke had a narrow escape that took place when he was on a ferry, returning home from work. A crewmember slipped and fell overboard, taking Konosuke with him. As he struggled to stay afloat, Konosuke could see the ferry was already a considerable distance away. Luckily it was summer, and he was quickly rescued. This convinced him that he was "naturally lucky" and able to recover from setbacks.

Konosuke is hired as a technician's assistant at Osaka Electric Light Company. In just three months, he is promoted to installation technician for his skill in wiring.

Konosuke is hired as a technician's assistant at Osaka Electric Light Company. In just three months, he is promoted to installation technician for his skill in wiring.

Put in the hard work first

One Osaka summer, Konosuke was on his way to a wiring job at an old temple in the Shitadera-machi area. The work required him to climb up into the attic of the main hall, where it was pitch black and extremely hot. The temple was around two centuries old, and the attic had accumulated a layer of dust as much as three centimeters thick. As Konosuke walked under the roof, he raised huge clouds of dust with a puffing sound. It was a truly hellish worksite, yet Konosuke was so preoccupied with finishing the work that he forgot about the dust and perspiration and choking conditions.

An hour later, when he descended from the attic, he experienced an indescribable feeling of freshness. The air outside the attic, which before had seemed hot, now had a heavenly coolness. He realized that even difficult, painful conditions could be forgotten if he focused on the work at hand; and once the work was done, he experienced a feeling of extreme joy.*

*Konosuke mentions this experience in a number of his books, including Message to Youth (Japanese only).

Konosuke leaves Osaka Electric Light Company and strikes out on his own.

Konosuke leaves Osaka Electric Light Company and strikes out on his own.

"I want to manufacture my socket with my own hands": Goes independent with only 100 yen in capital

At a young age, Konosuke had become a supervisor, but he soon felt his work was not challenging enough. At the same time, his constitution was not robust, and he sometimes had to take sick leave. In those days wages were paid based on days worked, and so he thought he was not well suited for a salaried life. But his main incentive for becoming independent was his boss's cruel dismissal of the improved electrical socket prototype, which Konosuke had designed himself and for which he had received a utility model patent right, as "no good." Konosuke wasn't sure he could succeed, but he strengthened his courage by resolving, "If it doesn't work out, I'll go back to work for Osaka Electric Light Company and spend the rest of my life there as a loyal employee." With less than 100 yen* from his severance payment and the money he had saved, Konosuke, his wife Mumeno, her younger brother, Toshio Iue, and two colleagues who left Osaka Electric Light Company to follow him, began preparations to manufacture the socket. But this task proved to be more difficult than expected, and it took four months of trial and error before the problems were at last ironed out.

*For comparison, starting monthly salary for an elementary school teacher at the time was around 40 to 55 yen.

Second row, from left: Konosuke, Toshio Iue, and Konosuke's wife, Mumeno

The crisis is resolved when Kawakita Denki commissions Konosuke to manufacture electric fan insulation plates.

The crisis is resolved when Kawakita Denki commissions Konosuke to manufacture electric fan insulation plates.

(Left: contemporary ceramic plate. Right: plate made from plastic compound)

Keeps going until he succeeds: Overcoming early challenges

Konosuke had taken the first step, the manufacturing of his socket. But he had no sales channel, and knew nothing about setting prices.

After ten days spent visiting electrical equipment shops and wholesalers, Konosuke's salesman had sold only 100 sockets, for less than 10 yen in proceeds. People who declined to buy had such comments as, "I've never seen anything like it. Who will repair it if it breaks?" "I've never heard of your company." The effort was a complete failure. Making the product better was not an option: Konosuke's capital was almost gone, and tomorrow's living expenses would not wait. The two colleagues who had followed him from Osaka Electric Light Company were forced to look for work elsewhere.

But Konosuke did not give up. As the end of the year approached and there still was no income, he received an unexpected order from an electric equipment supplier for electric fan insulator plates, earning him his first profit of 160 yen. The introduction came from one of the wholesalers he had contacted during his effort to sell the socket. Though the socket did not sell, his effort still resulted in unexpected good fortune. Konosuke looked back on this experience:

"Even if what you are waiting for does not arrive, a path through your dilemma will appear as conditions around you change; or perhaps others will appear to offer support and help, enabling you to find a path to considerable success, though it may be quite different from what you planned."

Konosuke founds his company.

Konosuke founds his company.

Konosuke launches the bullet-shaped battery-powered bicycle lamp.

Konosuke launches the bullet-shaped battery-powered bicycle lamp.

Staking the company's survival on a daring sales tactic: Using the product to promote the product

Having gotten his electric wiring fixtures business on its feet, Konosuke began developing a battery-powered bicycle lamp. He immersed himself in the research and development of the new lamp, and finally succeeded in creating a revolutionary product that ran for more than 30 hours, ten times longer than conventional battery-powered lamps. "This is a superior product. It's sure to sell well," Konosuke thought, but in fact things did not go so easily at first. Battery-powered lamps at the time malfunctioned often and were not economical. Wholesalers did not welcome them, and even when Konosuke explained the advantages of his lamp passionately, they were not convinced. Though he visited every wholesaler in Osaka, the lamp did not sell, and his ballooning inventory sat idle.

Rather than give in to discouragement, Konosuke decided that the wholesalers were refusing his product because they simply did not understand true value. His solution was to visit retailers, who were closer to the end user, and leave samples of his lamp with them at no charge. He asked them to test the lamp in their shops, and to buy it from him if the results were positive. This was a dangerous gamble for Matsushita Electric given the company's lack of capital, but it paid off. Once they understood the product's value, orders from retailers rose day by day, and the wholesalers had no choice but to stock the lamp too. Konosuke was thus an early practitioner of marketing strategy.

Konosuke launches National Lamp.

Konosuke launches National Lamp.

The birth of the National brand: First newspaper advertisements

Four years after the launch of the bullet-shaped battery-powered bicycle lamp, in the Showa Era, Konosuke launched an even more compact, square-shaped battery lamp. His plan was to make the lamp an indispensable item for people everywhere in Japan, and with this in mind he christened the product with the English word "National," somewhat after the fashion of the "People's Car," the German Volkswagen. And for the product launch, Matsushita Electric used newspaper advertising for the first time. Konosuke penned the ad copy himself: "Reliable Quality, Superb Value, the National Lamp." From then on, he placed great emphasis on advertising and promotion, because he believed it was "the responsibility of the manufacturer to make quality products and communicate that quality to customers quickly."

Konosuke Matsushita, inventor: "I want to manufacture products that make people happy"

Konosuke Matsushita, inventor: "I want to manufacture products that make people happy"

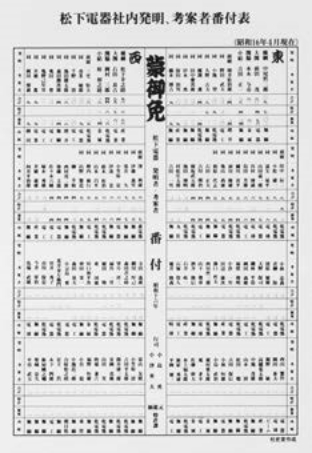

During his life, Konosuke was awarded eight patents and 92 utility model patent rights. In Matsushita Electric's early years, he was both entrepreneur and inventor. He submitted his first application for a utility model patent right in 1916, for the improved socket he invented at Osaka Electric Light Company, and his first patent application in 1926, for a voltage regulator.

When he was working on the idea for an invention, he almost forgot to eat and sleep, and always kept a notebook by his pillow. Even after the scope of his business expanded, he took advantage of every free moment from his management work to take his products in his hands, sketch them and add improvements.

Konosuke always spoke to new employees at entrance ceremonies and training.

How did he express himself? What did he call on them to do?

We take a look back, drawing on the contemporary business and social environments.

You are presidents of an employee-as-entrepreneur business

To hold a job in society essentially means you are independent. Each of you is running a company whose business is "employee entrepreneurship." It is very rewarding to view things from such a high-level perspective.

Our employees all hold independent occupations in which they are responsible for providing a service that consists of themselves as employees. That is the independent occupation of those individuals. As far as their occupation is concerned, they are company presidents. I believe we must all work diligently, adopting this high-level perspective.

New Employee Induction Training, April 1962 (age 67)

Refine your mind and grow

We can change the way we perceive things by changing the way we think. One moment we might think that we cannot bear our hardships any longer and may as well lay down and die. And yet, we can change, so that the next moment we somehow pluck up enough courage to feel that we can take on the world.

This is why I believe that when you take on the challenges of various tasks in your work, you must first refine your mind and spirit and grow in the way you think. When people look at the same thing, some are able to see only a very small part of the picture while others can see it as a whole. Some people have 180-degree vision and some have 360-degree vision. And some people can even stand in one place and sense what is in the back of them. If you can combine the knowledge you have acquired until now with this way of thinking, you are sure to achieve profound outcomes. These will be outcomes that will contribute to the development of our company and to your own personal development and prosperity.

New Employee Induction Training, April 1964 (age 66)

Matsushita Electric at the time

Around this time, Matsushita Electric had fulfilled the targets of its Five-Year Plan (1956-1960) and was on the way toward growing its business further, including international expansion. Consequently, its workforce was growing rapidly, and Konosuke emphasized that each employee should render service to society through his or her work for the company, acting as independent entrepreneurs rather than viewing themselves as salaried workers. In addition, in May 1962, the company began giving new employees internship experience at affiliated retailers, where they could learn the frontline fundamentals of the merchant.

The contemporary environment

Global tensions and Japan's "irresponsible" era

The previous year, in 1961, President John F. Kennedy delivered his famous inaugural address.

"Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country."

That same year in April, Yuri Gagarin became the first man into space aboard the Vostok spacecraft. In Germany, the Berlin Wall went up, and the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union deepened. As global tensions worsened, Japan's rapid economic growth was making life more and more affluent, and being a salaried employee was seen widely as a comfortable occupation.

Konosuke's messages to new employees must have reflected these social conditions.

Our company uses the talents of our young people correctly

One of the most outstanding aspects of our company is our correct and thorough use of the talents and energy of our young people. Work is taken on wholeheartedly by young employees of our company in a way not seen at other companies. No matter how big a project we have, I am always confident that we can bring construction to completion with the abilities and energy of our young people. Older people may be adept at completing work but sometimes they have a tendency to be excessively meticulous and are often slow to finish. The young, on the other hand, are fact in their work and they pursue it with zestful enthusiasm. Recently I feel that the tendency to see things in a critical light is growing stronger. It is fine to be critical of things to a point but ultimately, we all must believe in something. The thrill of truly believing in something—this is what generates great talent and energy.

At a discussion meeting held by the president for new employees, May 1936 (age 41)

Matsushita Electric at the time

The year before he gave this speech, the founder had reorganized Matsushita Electric Works as Matsushita Electric Industrial Co., Ltd. The company was at the peak of its prewar prosperity. Its businesses were growing extremely rapidly, and to extend the National brand across the globe, the founder turned his sights on international markets. In the same month, May 1936, he sent three of his senior managers, including Tetsujiro Nakao, to the US on an inspection tour. When they returned home, Nakao wrote in the company's in-house newspaper, "Seeing Matsushita again after being away from Japan, I find myself astonished. I was struck anew by the realization that the attitude of our employees, working diligently in line with a firm credo, and the rapid development of the division companies, have no parallel in any other country." The energy of the young was no doubt fundamentally essential to the company's growth following Meichi, the revelation of the corporate mission.

The contemporary environment

Amid a drawn-out slump

The February 26 Incident, the most serious attempt at a coup d'état in modern Japanese history, also occurred in 1936. It came amid a deep economic slump caused by the ongoing effects of the Great Depression, and was due to despair on the part of young army officers at the Japanese government's clumsy response. During this period, Matsushita Electric overcame numerous challenges and grew by following its mission, testifying to the truth of Konosuke's statement that "Our company uses the talents of our young people correctly."

Understand the difficulty of making profits

You have now gained actual experience, for a short time, working in affiliated retail stores or similar environments. You have seen how the managers of these stores deal directly with consumers, collect payments, and as a result, generate a certain amount of profit. I believe you have experienced just how difficult that is to achieve. I suppose that few of you have so far had the opportunity to make profits yourselves. […]

But you entered the company and were posted to a retail store, and you watched as the owner, or his spouse or a sales clerk, sold products and made profits; and you realized for the first time how much commitment that requires […] and how difficult it is to make profits.

In the future, no matter where you are posted or what sort of work you do, don't forget these lessons. You must keep them in mind at all times. This is how your business sense will grow and develop.

Address to new employees, October 1968 (age 73)

Even when competing, maintain an untrapped (sunao) mind

It is because of competition that people learn, and aiming to make progress, they grow and develop. I think this is truly splendid. But as you compete, you must maintain a sunao mind. Otherwise, you will be unable to grasp the true nature of the situation, you will make mistakes and accumulate mistaken views, and these will cause you to lose in competition. […]

So far Matsushita Electric has generally not lost in competition. Not that we've put winning above all else, but we've judged sincerely which course of action was the best, and followed that path with vigor. That is our competitive approach, and we always aim to create positive outcomes. I think this approach results in victory when competing. I'm convinced that this is what results when one sees society, sees the company itself, and sees the situation, all with a sunao mind.

Address to new employees, October 1968 (age 73)

Matsushita Electric at the time

Matsushita Electric celebrated its 50th founding anniversary in 1968. The Matsushita Electric House of History (today's Konosuke Matsushita Museum) opened its doors on March 7 of that year. It was also in 1968 that a decision was made to exhibit the Matsushita Pavilion and the Time Capsule EXPO '70 at the world expo in Osaka two years hence. A wide range of 50th-anniversary activities of the company were carried out, including a donation totaling five billion yen to the Children's Traffic Accident Prevention Fund, and construction of factories in underpopulated areas. Alongside these initiatives, the company also turned its business activities toward contributing to society in earnest.

The contemporary environment

Emerging social problems and the baby boom generation

Around this time, pollution and the environment came to the fore as problems in Japan. The number of fatalities in traffic accidents exceeded 15,000 (reaching a peak of 16,765 in 1970), prompting people to speak of "traffic wars." Another major problem was the rising population in large urban centers and rural depopulation. These were the factors behind Matsushita Electric's active social contribution activities.

At that time, the baby boomers were newcomers to the workforce. The student movement and turmoil on campuses were led by this energetic cohort of young people. Due to the large population, this generation had been forced to compete with each other. But at the same time, they had known nothing but affluence during Japan's postwar period of extreme economic growth. The new employees coming into Matsushita Electric must have heard Konosuke's message as a wake-up call about the challenges they would face in the world of work.

"I love communicating with young people."

Konosuke said this at an interview.

This was his sentiment toward youth everywhere.

Let's look at some of what Konosuke said to the youth of Japan, a group of young managers and company presidents from around the globe.

The businessperson's duty is to be loved

Q: Though you've been extremely successful, you seem to be a very modest person. How do you maintain such a modest, humble attitude?

"I don't pay attention to whether or not I'm being modest. But ultimately, I think situations require one to tap into the collective wisdom of others. If there are ten people, you draw on the wisdom of all ten. The same applies if there are a hundred people. My approach is that even if there were a hundred million people, I would seek to learn from each one of them. So everyone here, and this building, and these lights, and everything else can teach me something. That's how I approach it. Therefore, everyone around me is more accomplished. I'm at the bottom. That's how I see it."

Q: What is the most important task of a businessperson?

"Simply put, it is to be loved by everyone. The businessperson must be loved by everyone. People should want to buy your products with the trust that it is to you who made them. To achieve this, a spirit of service is most important. If you don't have a drive to serve others, people won't want to buy products from you. Consequently, the businessperson's most important task is to be loved by others. Their work should be loved by others. If you can't do this, you're not suited to be a businessperson. You're sure to fail."

Konosuke says that the duty of the businessperson is to be loved, and that to achieve this a spirit of service is necessary. It is this outlook that leads to the principle that "The customer comes first." Konosuke learned the fundamentals of business as an apprentice at Godai Bicycle Shop in Semba, Osaka, where he witnessed his master Otokichi treating his customers extremely well—asking them about the functioning of the bicycle they'd purchased, rushing to help if they were in need, and always doing business with a spirit of service. In addition, when Konosuke himself sold a bicycle, he experienced firsthand the importance of being loved. One can see how the principles he mastered as a youth become his foundation as a manager.

At this event, which was attended by young company presidents from around the world, Konosuke first read "Advocating a New View of Humanity," a passage from his book Thoughts on Man, published in 1972. As he spoke through an interpreter, now and then drawing laughter from his audience, Konosuke seemed the epitome of an "international person."

Passion is fundamental to management

Q: Could you say something to managers, especially young managers, during these turbulent times?

"I do think the state of the world is very difficult. But these challenges are not faced by one person alone. To put it differently, you can't expect things to go well for yourself only. You need to be resolved to take your lumps along with everyone else. That attitude often results in things going better than expected. When people collaborate, they come up with ways to cope naturally.

It's one kind of inspiration. You have to have something like that, you need to learn it firsthand. If you do, you don't need to have the inspiration or the judgment of a genius. If you use common sense, I believe that's enough, speaking from my own experience. In fact, the correct path is often quite simple. […] I'm now in my eighties, but I'm simply doing my best, in my own way, to move forward against the storm. I neither run away nor hide from the rain. You young executives have much more energy than I do. Let's join hands and move forward together. If we get wet, we get wet, that's how I see it."

Q: What is the knack for achieving a breakthrough when you find yourself blocked and unable to move forward?

"When you find yourself in that situation, drop all of your preconceptions and return to the basics, and examine them once again. Managers must always act in good faith. You may or may not be articulate, but I think one should always speak from the heart in each instance. […] When you have a sincere attitude, you'll always be persuasive, even if what you say today is very different from what you said yesterday. […] If you speak in a calculated way, I don't think you can be a real manager."

Q: You said that passion is fundamental to management. But passion is a momentary condition. How can it become a driving force for management?

"With passion, you learn to look ahead, and your passion inspires others to work diligently. No matter how clever you may be, if your management lacks passion, you can't motivate the people around you. They won't work to the same end. Channeling people's hearts and minds also depends on whether or not you have passion. Passion is the major determinant. People won't follow you because you work hard and you're an expert. Instead, they're impressed by your passion, and convinced to follow you."

A series of articles in Three Billion (Japanese only) from January through December 1976 (age 81)

Japan's rapid economic growth ended in the 1970s. The first oil crisis came in 1973. In 1974, Japan's economy posted negative growth for the first time in the postwar period. Moreover, the problem of pollution worsened. "Neither run away nor hide from the rain. If we get wet, we get wet." "Drop all of your preconceptions and return to the facts." These words, spoken by Konosuke when he was 80, apply as well to the difficult challenges of today, and help us understand how to search for a path to solutions.

Overcome ego

I've been managing people for many years, with numerous ups and downs, but overall things went well. Sometimes, however, I make mistakes. People I thought were reliable sometimes succeed and sometimes failed. When I tried to boil down the difference between the two, the ones who failed were acting on the basis of ego, while those who succeeded were acting selflessly. Both types were equally intelligent. But when a bit of ego enters in, the difference between this is considerable. […]

Personal ambition can be a factor even with old people such as myself. I would suppose that energetic young people like you would be even more ambitious in all sorts of ways. And I think ambition is important. But ambition can be 'public,' or it can be 'private.' […]

I myself am 80 years old, but I still struggle between private ambition and public ambition. Even if I feel I should act in a public capacity in a certain situation, the next moment my private ambition comes to the fore. It's hard for human beings to shake this habit. You may notice your ego and suppress it, but it always returns. This is a problem you will face until the day you die, you can't escape it. But if you can somehow control it throughout your life, and I think you will become a wonderful person.

At the Junior Chamber International Japan, Nagoya, 1976 (age 81)

Even in his eighties, Konosuke continued to admonish himself, and was always alert to the presence of ego. Even with the same capabilities, some people fail and some succeed. The difference depends on the presence or lack of a self-interested "I." Putting it differently, success depends on having a sunao mind. In Konosuke's view, the mark of a sunao mind is a lack of personal ambition, the capacity to see things as they are, and judge value correctly. Konosuke himself must have struggled every day to maintain his sunao mind.

Learn from your mentors and teachers

What sort of person was Kobo Daishi? I never met him, of course, but according to what I hear, he was an extremely outstanding Buddhist priest. Even Kobo Daishi, when he was young, was ignorant of many things. He followed his teachers, developed himself, and followed the correct path.

By all means, think carefully about what you are suited for and what path you ought to follow. At the same time, learn from others. Learn from your mentors and your teachers. Combine your own perspective with that of others so you can plan your correct path. I believe this is what you must do. In my business, I've been fortunate to receive the patronage of many people, and so I continue to do what I do. Still, I face uncertainty every day. […] When that happens, I ask others for advice. I think this is the best approach. Ask those you trust for advice.

Special lecture at Gunma Prefectural Takasaki High School, 1964 (age 69)

Success is built day by day

Today, you have become adults at last. As you pursue your dreams, there is one thing I would like you to keep forever in mind.

There is a famous old quote that goes, "Boys, be ambitious!" This is something very important. […] Yet I have a feeling one should avoid being carried away by words alone. […] Actually, when I look back at myself when I was about 20, all I had was a simple desire to make ends meet. […] But 50 or so years since then, while I can't say that I have been successful due to some great ambition, I think by meeting every day's challenges diligently, I've been just as successful as I would have been had I worked with great ambition. […] I think ambition can often cause you to look out into the distant future while neglecting the things you need to take care of today. Some might say that ambition is the enemy of success. There are some who eschew ambition, focus on achieving good results every day, and ultimately achieve just as much success as some who are ambitious. As for myself, I would say that I'm not ambitious, but I suppose I've achieved as much success as someone ambitious.

Kadoma City coming of age ceremony, 1967 (age 72)