The Hall of Manufacturing Ingenuity closed on Friday, December 26, 2025.

●Regarding Group Reservations After January 2026

Due to the transition to single-museum operation at the Konosuke Matsushita Historical Museum, capacity restrictions will be implemented. Therefore, to ensure a safe, secure, and comfortable visit, we will discontinue accepting group reservations starting January 2026.

Additionally, admission may be refused depending on crowd levels within the museum.

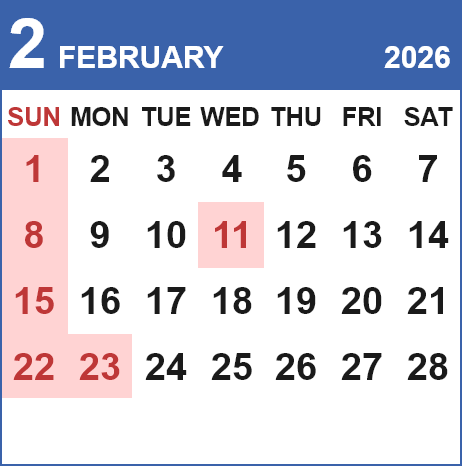

●Notice of Opening Day Change

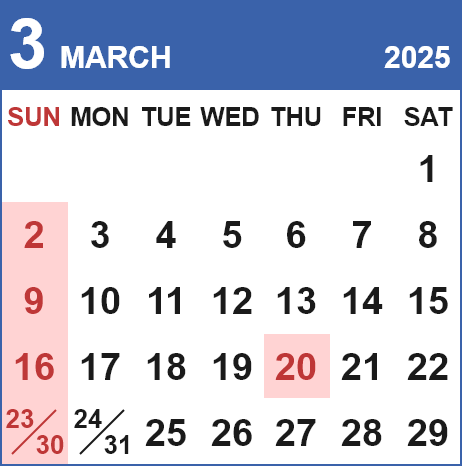

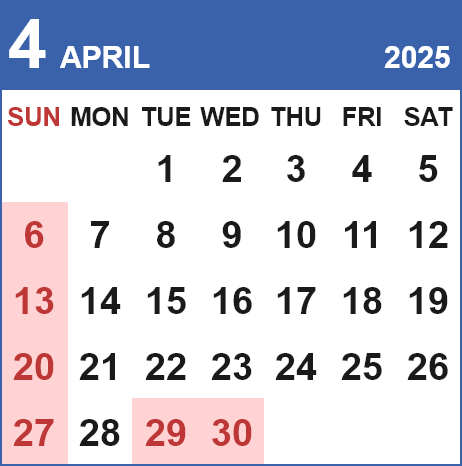

Starting April 2026, the museum will be closed on Saturdays. Accordingly, the museum will be open Monday through Friday. Please check the opening calendar for specific dates.

We apologize for any inconvenience this may cause and appreciate your understanding.

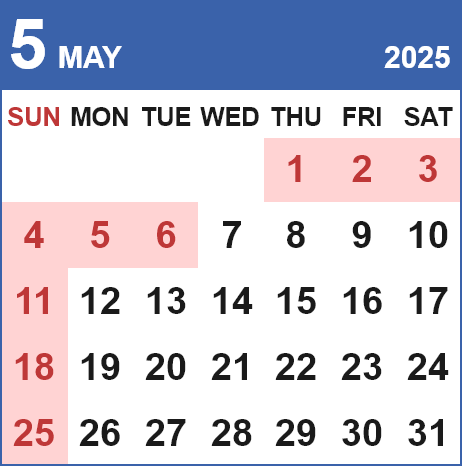

Calendar

Greetings

The founder of Panasonic, Konosuke Matsushita, established a management philosophy stating that a company is a public entity of society, and put into practice his belief that a company must contribute to society through its business operations.

At the same time, he strove to go beyond the conventional role of a businessman and realize his desire for the prosperity and happiness of humankind.

More than 100 years have passed since the company's foundation in 1918.

During that time, later generations have continued to inherit the ambitious goals, approach and philosophy of Konosuke Matsushita, who continually strove for A Better Life, A Better World, and created numerous products and technologies, fostering a corporate culture unique to Panasonic.

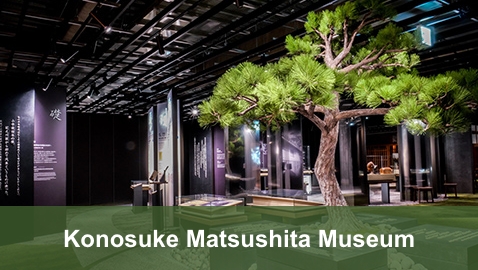

The Panasonic Museum was established to convey our appreciation for society's support over the past 100 years and to pass down the passion and spirit of Panasonic to future generations by showcasing Konosuke Matsushita's words and Panasonic products from the past.

In this place where everyone can learn, we hope you will find some clues for your own approach and philosophy.

Society, economics, industry. In this multi-faceted era of change, Panasonic hopes to continue to be a company that contributes to the development of society.

We sincerely hope that you will be able to come and visit us. We look forward to seeing you.

Facility Guide

Address:

1006 Oaza Kadoma, Kadoma-shi, Osaka, 571-8501, Japan

Access:

About a 2-minute walk from Nishisanso Station on the Keihan Line

Admission fee:

Free

Hours:

10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m.

Closed:

Sundays, Public holidays, Obon holiday and New Year holidays, Holidays set by Panasonic Museum

*Closed on Saturdays starting April 1, 2026.

Parking:

Spaces for 10 cars and 4 large buses

*Parking is limited. We recommend the use of public transportation.

Bicycle parking:

Limited space available